Racial bias and representation in the arts in Britain, has anything changed since the 70’s?

- George

- Jan 27, 2023

- 31 min read

Updated: Nov 20, 2024

Contents/Intro:

In this paper I wish to examine the extent to which racial bias has affected the amount of visibility afforded to black artists and their work. I’ll ask the question “has anything changed since the 70’s?”. My argument begins with a look at the conditions which led to the absence of Black British artists in the wider arena during the ‘70’s. I’ll discuss inherent bias built into the arts focusing on those who hold the power and ability to influence decisions in the art world; gallery owners, curators and sponsors, who appear to support and maintain outdated and Eurocentric values. I will offer my opinion on what measures can be taken to redress the balance in arts education which struggles to engage more people of colour to join its teaching staff and student base. My study will consider the efforts of those struggling to break through the colour bar and seize opportunities, and conclude with a look at the measures in place (or planned) to increase representation and visibility within our galleries, museums and within the industry as a whole.

1 The Great British Whitewash

In order to discuss the extent to which the UK has largely excluded its black population’s contribution to the arts, I must first look at how African-Britons have been eradicated from the art history books despite being a visible part of British society from as long ago as the Roman times. Acknowledgment of black bodies in paintings of the time has often been limited, in place of a name you are more likely to be offered a description usually given to everyday items such as furniture; 'A Negro' or 'A Servant' for example. (Joseph, 2019) This objectification of the black body continues to this day and has been the focus of some heated debate. The actor Paterson Joseph voiced his outrage at this practice in an article for Art UK, ”African-Britons have largely been whitewashed from the record of British art history, simply because those charged with recording this history were not minded to include them...” (Joseph, 2019), pointing to art historian John Madin and his article entitled ‘The Lost African, Slavery and Portraiture in the Age of the Enlightenment’ which appeared in the international arts magazine Apollo in 2006. Madin lays out the conditions in which the identity of a particular sitter in a 1759 portrait by King George III’s personal painter, Allan Ramsay, was largely considered to be that of Nigerian writer and abolitionist Olaudah Equiano (Madin, 2006). Equiano was enslaved from childhood but later managed to buy his own freedom and transform his fortunes through his literary prowess. Although a plausible candidate for this privilege, examination of the timeline would eventually result in many historians concluding that Equiano could not have been the subject of the portrait; he would have been too young and still a slave at the time, and therefore an unlikely choice of subject for someone of the Ramsay’s standing (Madin, 2006).

Scholars then turned their attention towards the ‘British’ abolitionist Ignatius Sancho as a more plausible candidate; Madin proclaimed that “he (Sancho) was probably better connected than any other African in the country and, crucially, of the correct age for the portrait. His circle is known to have included the literary and artistic élite of London and he was employed and supported by one of the wealthiest aristocratic families in England” (Madin, 2006). Such a vindication of Sancho’s character was enough to satisfy the art historians that he was indeed the sitter and although there is still some contemplation over the true identity the argument has largely been laid to rest (although Allan Ramsay’s 1759 portrait still appears attributed to both Equiano and Sancho when conducting a Google search).

The debate goes some way to highlight the manner in which black lives, even in the arts, were not deemed worthy enough to be properly catalogued outside of the records meticulously kept by their slave owners. To add to the complexities slaves were routinely re-named by their owners (Olaudah Equiano was renamed Gustavus Vassa by his then owner Michael Henry Pascal) (Equiano, 2015 p. 30) thus adding to the confusion surrounding the issue of accurate identification. In Madin’s response to Joseph’s impassioned cry for the arts community to try harder he wrote “These people are dressed and (most importantly) depicted as servants, whether singly or within groups. For the most part, they enjoyed neither social status nor individual rights and for this reason, historical records of their identities and personal stories are rare.” (Madin, 2019). This sits uncomfortably with me as both held success in their own rights; both were published writers, in addition Sancho was a composer and actor, as well as being the first Black Briton to have voted in a general election. Both were gentlemen with credentials enough to be considered as a worthy subject for such a portrait, also the garments worn by the sitter, whether it be Equiano or Sancho, do not appear to be typical of those adorned by slaves.

Georgian London was home to approximately 20’000 people of African descent, many enslaved, yet still providing valuable contributions to the nation’s history, economy and cultural identity. In a period where slavery was reluctantly becoming outlawed owning a black servant was seen as a status symbol and many of the more affluent households flaunted their wealth through such practises. Conditions were arguably better for the new servants; some were even afforded some form of payment for their services although this rarely amounted to much. Ultimately, these ‘citizens’ were still largely regarded as little more than chattel, items that can be passed from owner to owner, as was often the case with those born or thrust into slavery. It then leaves little resistance to the fact that art history failed in its duty to record the lives and contributions of black artists of the day, and in this absence of historic reference it’s easy to understand how current day aspiring black artists struggle for recognition in a field where they have never been made to feel as though they belong.

2 The Burden of Invisibility & Obligation

This lack of willingness to account for the contributions of minority ethnic artists plays into the fact that there still appears to be no credible records of how long black artists have been practicing in the UK (Chambers, 2014, p. 1). In his book ‘Black Artists in British Art: A History from 1950 to the Present’ historian and author Dr Eddie Chambers wrote “There is a terrible burden of invisibility and eradication that history has bequeathed the black British artist" (Chambers, 2014, p. 2). As far as documenting the contributions of black artists’ is concerned, Chambers points towards the black sailor Joseph Johnson (aka Black Joe) as a possible candidate for this accolade (Chambers, 2014, p. xiv). Johnson is documented in 1815 in an image by John Thomas Smith wearing a model of the merchant navy ship Nelson on top of his hat (Chambers, 2014, p. xiv). Such adornments were commonplace in some West African dances and could be seen as the source of Johnson's inspiration. Black Joe sculpted the model himself in great detail and to this Chambers argues that Johnson could well be the first black sculptor to be recognised as an artist on British soil (Chambers, 2014, p. xv). Even though there remains little doubt that a reasonable number of black practitioners existed in that period and beyond, searching for records of their existence has proven fruitless; any reference to them and their work appear to have been obliterated from the annals of art history. This practise continues even to this day; many of the ground-breaking exhibitions of the 70’s to feature black artists for example have gone almost undocumented, essentially forgotten. The occasional university archive or publication like Eddie Chambers’ ‘Black Artists in British Art…’ play a major role in preserving their rightful place in UK art history.

I also found limited information available on the various organisations that formed in the 70’s; centres like the Keskidee Arts Centre, formed in 1971 and the brainchild of Guyanese architect and cultural activist Oscar Abrams (Chambers, 2014, p. 51). Abrams had a vision of a safe-place for artists of colour where their practises and output would be valued and respected. The centre provided a gallery space offering black artists otherwise difficult-to-obtain opportunities to display their art, alongside a library (where Linton Kwesi Johnson worked as a resources and education officer) and theatre. Perhaps the most high-profile endorsement of the centre’s importance came from its use by Bob Marley in his video for the 1978 hit "Is This Love?”. Keskidee was a pioneering hot-spot for the black arts community and enjoyed a period of success, however the 80’s saw the centre run into financial difficulties and its doors finally closed in 1992 (The Keskidee Centre, 2020). One of the many beneficiaries of Keskidee’s existence was the ground-breaking Caribbean Artists Movement, who held regular events and exhibitions at the centre. The group, viewed as “the first organised collaboration of artists from the Caribbean with the aim of celebrating a new sense of shared Caribbean ‘nationhood’” (Lloyd, 2018) was formed in 1966 by John La Rose (activist, writer, publisher and founder of New Beacon Books), Kamau Braithwaite (poet and historian) and Andrew Salkey (writer and broadcaster) (Lloyd, 2018). CAM’s membership included those, black and white, who shared a common desire to support the arts rooted out of the Caribbean; an event night could see aspiring artists, musicians, poets and actors share the same space as academics, activists and the curious. It was an exciting time and an inspiring cathedral to a community largely excluded. The artist Roy Caboo, born in Trinidad, enjoyed a nine-month residency at Keskidee in which he was granted access to studio space and equipment, his time at the centre led to an exhibition and a feature in the equalities journal ‘Race Today’, the piece spanned four pages and featured an interview with Caboo in which he acknowledges the role Keskidee played in kick-starting his painting career (Chambers, 2014, p. 5). Frustratingly I was unable to find any of Caboo’s work to feature here, or indeed very little about the artist himself, which further illustrates the great vacuum that envelops many working artists-of-colour of the period.

Throughout the 70’s, 80’s and 90’s attitudes towards black people in the UK were fuelled by racial tensions and proving to be largely problematic, much of the output from black artists would have been viewed with suspicion and labelled confrontational or too political. Black artist found themselves the victims of marginalisation which served to protect of the legacy of the country’s white mainly male artists, curators, gallery owners and historians at the expense of the contributions from those considered ‘others’. By keeping black artists on the periphery there was less of a likelihood they could ‘muddy the water’ with their visuals which were clearly at odds with the Eurocentric default; this increased suspicions amongst black artist that they simply did not belong to the club. Prior to the 1980's black artists were routinely referenced by their originating nation; an Afro-Caribbean artist, an African artist, an Asian artist, but never a British artist (Chambers, 2014, p. 1). Even with the dawn of ‘ethnic arts’ in the UK in the mid 1970’s black artists were in large part expected to produce work specific to the black experience in order to be taken seriously and exhibited in galleries, usually as part of a group exhibition with its focus on afro-centric art. Individually, there was little regards for the offerings of minority ethnic artists, theirs was an art form seen as not fitting the British arts agenda. Naseem Khan mirrors this sentiment in his scathing report ‘The Arts Britain Ignores’ in which he suggests that Ethnic Arts is laden with its own limitations, including a tendency to “conjure up associations of ancient cultures embedded in the souls of Black people” (Khan, 1976), such an allegation places the black artist outside of the realms of modern and contemporary art by virtue of the content and tone of their work, the opposite is evident for the white artist who has no such obligations thrust upon their work. To this Rasheed Araeen wrote in his critique of the 1978 exhibition ‘Afro-Caribbean Art’ at the Drum Centre;

“Just because an art is produced by somebody who is of Afro Caribbean origin, or for that matter from Africa or the Caribbean, does not itself lend to that art an Afro-Caribbean particularity unless that particularity is expressed in the work itself, unless the work reflects upon or deals with a reality which in turn necessitates the work to be called 'Afro-Caribbean Art'.” (Chambers, 2014, p. 48)

As already discussed the arts community’s lack of engagement with ethnic arts, and the debilitating lack of exposure led marginalised black artists to band together forming collectives, the output of which usually centred around issues of identity and the black experience within the UK. Collaborations such as the BLK Art Group, formed in the Midlands, introduced the world to the work of artists including Keith Piper, Marlene Smith, Eddie Chambers, Claudette Johnson and Donald Rodney. (Sinclair, 2020) The BLK Art Group came into existence in 1979, a period that saw growing racial tension on the streets fuelled by Margaret Thatcher’s immigration policies and worsening unemployment rates. The political mood meant that these children of the Windrush generation, whose forefathers were initially invited by the government, found themselves caught up on the frontlines of the battlefields as the proverbial hit the fan. Much of the groups output would be informed by personal experiences and the impact of the black presence in the UK, offering anyone open to enlightenment an insight into what life in the UK was like for the unwelcomed outsiders. The country’s art establishment did not perceive the work of collaborations like BLK Art Group to be in fitting with the nation’s portfolio resulting in BLK Art Group (and others like them) staging their own exhibitions, organised, funded and publicised by themselves. Eddie Chambers, himself a respected artist of the period, offers more insight;

“Firstly, these artists pretty much had nowhere else to go, and no other umbrellas under which to exhibit. Secondly, the societal status quo that had emerged in Britain by the mid-1970s was one in which Black people were, at best, assigned the status of societal problem.” (Chambers, 2014, p.41)

As ill feelings continued to spill out into all corners of society including the institutions of education, law enforcement, the workplace and the media Chambers concludes “With the wider society apparently reluctant to accept Black people as equals, it was perhaps not surprising that the art world was to follow suit in such emphatic fashion.” (Chambers, 2014, p.41)

3 Life After Death

In 2019 the work of Guyana-born Frank Bowling was the focus of a long overdue retrospective at the Tate Britain. The exhibition featured a collection of Bowling’s finest work including his large scale iconic map paintings produced between 1967 and 1971. Bowling, a former student at the Royal College of Art (where he studied alongside David Hockney), became the first black artist to be elected a Royal Academician in 2005 (Fullerton, 2019); this, together with his output which has been held in high esteem throughout his career places him firmly in the category of artists’ worthy of such attention. Yet the fact that this happened during his lifetime signals a slight shift from old trends of bestowing recognition after death. Bowling remains an exception to the norm, it’s not difficult to find evidence supporting the suggestion that way too many of the country’s accomplished black artists (including Ronald Moody, Aubrey Williams, Anwar Jalal Shemza and Donald Rodney) are only awarded their rightful position in UK art history posthumously.

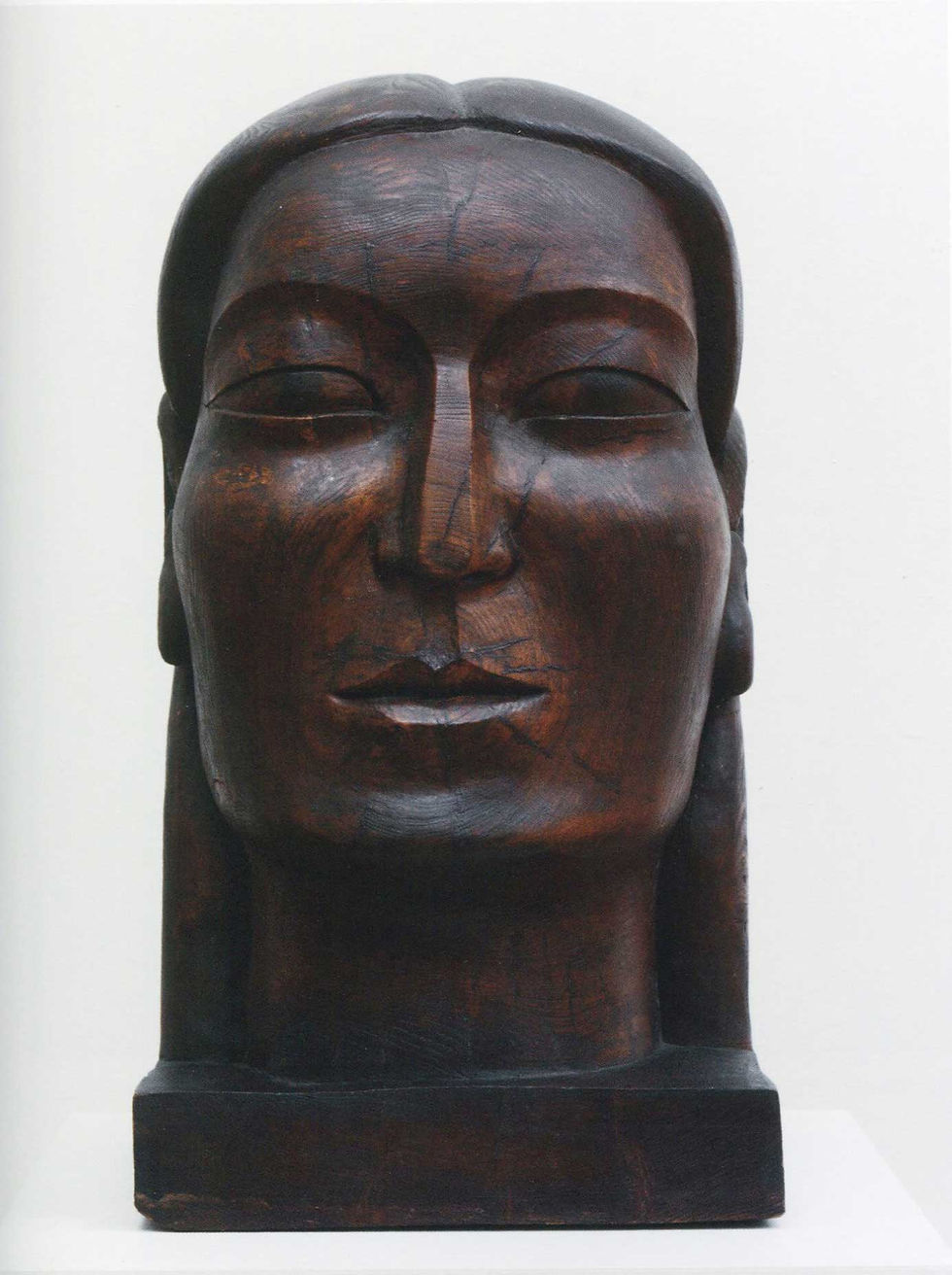

Ronald Moody was born in Jamaica in 1900 but moved to the UK in 1923 where under pressure from his family he studied dentistry and later opened a surgery in central London. A visit to the British Museum in 1928 sparked a desire to sculpt, his niece Cynthia Moody quotes him as saying “I knew that sculpture was the only thing I wanted to do…, nothing would prevent me from doing it, whatever the sacrifice and difficulties might be” (Moody, 1998, p. 10), and thus his journey into the arts began. Moody’s first piece was entitled Wohin, the 48 cm tall head carved in oak caused such interest that it was purchased by the writer and actor Marie Seton and later caught the attention of Brazilian filmmaker Alberto Cavalcanti who became instrumental in the arrangement of Moody’s first solo exhibition in Paris (Brett, 2003). Moody later moved to Paris where he remained until the outbreak of the Second World War imposed a hiatus on his creative ambitions. One of his favourite pieces was a large female head entitled Midonz, the piece was said to be instrumental in Moody’s transition from dentist to sculptor; it was during that fateful visit to the British Museum that Moody developed a passion and respect for Egyptian art, he spoke of the "tremendous inner force, the irresistible movement in stillness" (Moody, 1998, p.18) which he witnessed in the museum’s collection, this immeasurable influence led to the creation of his beloved masterpiece.

The Second World War saw Moody separated from much of his work, the impact on the artist was justifiably profound, although he was eventually reunited with 11 pieces he would never see Midonz again. Following his death in It was down to the perseverance of his niece, who had become the trustee of his archive after his death, wh and managed to locate the sculpture in the United States, that Midonz was able to resume its rightful place with the remainder of Moody’s creative collection. Cynthia Moody’s inherited role as guardian of her uncle’s estate was instrumental in the preservation of his legacy. Her loving treatment of his work led to a catalogue of the collection forming part of the Tate archives, and ultimately contributed to the 2004 retrospectives of his work at Tate Britain and Tate Liverpool, twenty years after his death. Freeing her uncle’s work from the grasps of marginalisation and placing Moody amongst the great British artists of the twentieth century became Cynthia’s mission up to her death in 2013, without her efforts Ronald Moody’s catalogue faced the prospect of being forgotten forever.

Aubrey Williams is another example of an artist whose acceptance into the ranks of greatness came years after his passing. Williams was born in British Guiana in 1926 and displayed an interest in art from an early age. He would however work as an Agricultural Field Officer for eight years before moving to the UK aged 26 in 1952 where two years later he embarked in studies at St Martin’s School of Art (Boyall, 2020). As a modern contemporary artist Williams enjoyed some recognition and considerable respect; his first show in the UK was a group exhibition at the Archer Gallery in London, his work was so favourably received generating rave reviews. He later landed his solo debut at the New Vision Centre Gallery, a space established by the South African born painter Denis Bowen (Chambers, 2014, p. 16). Bowen played a pivotal role in giving visibility to Williams and other abstract artists, in particular those from within the reaches of the commonwealth. Williams also faced the fact that the mainstream galleries were reluctant to accommodate minority ethnic artists whose work they believed had no audience. Williams held three solo shows at New Vision Centre Gallery and went on to exhibit at numerous established galleries until eventually the appetite for his work began to falter and he slipped into near obscurity. Williams’ treatment of the non-figurative received critical admiration in friendly art circles yet his catalogue remained largely unseen by far too many in the public. After some intervention by the influential art critic, writer and curator Guy Brett the Tate Gallery has acquired several samples of his work welcoming him into the fold. National archives including those at the Natural History Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum and the Arts Council England have joined the Tate and finally caught up. Aubrey Williams died in London in 1990, for the most part his career in the arts saw him marginalised into near extinction, its only since his passing that he appears a step closer towards infiltrating the psyche of British arts establishment.

4 The Shortcomings of our Education System

Tam Joseph's tryptic 'UK School Report’ perfectly illustrates the attitude of the education system towards black students in the 70’s and 80’s; a system which pigeon-holed many children of ‘Afro-Caribbean’ descent. I went to school in the seventies where boys were rarely encouraged to pursue the arts; the school’s career advisor (and admittedly my parents) preferring me to engage in more traditionally practical, manual and physical career paths, a mechanic or builder maybe. Opting for an arts based further education was seen as a waste of a future by some, or the easiest path to gain a degree by others. Attitudes have slightly changed since then; there appears to be less pressure on boys to take on ‘men’s work’ but the economic challenges remain for many working class families. The UK Cabinet Office website states that “black households were most likely out of all ethnic groups to have a weekly income of under £600” (Household income, 2022), leaving many unable to justify and support a £27’000 education. This coupled with the prospect of launching a new career in debt can be reason enough for many to choose alternative career paths. Those who do progress to university would have noticed the lack of black lecturers on campus, even today. A 2020 article in the Guardian highlighted that the number of black professors in UK universities amounted to an appalling total of less than 1% of the workforce, this figure only rising to 11% when Asian and other minorities are thrown in the mix (Adams, 2020). In terms of bodies most establishments could only account for a total of less than two professors on their payroll. The article’s author Richard Adams declared that “The Higher Education Statistics Agency (Hesa) figures show UK universities continue to increase academic and non-academic staff numbers to record levels but progress on employing more staff from ethnic minorities remains sluggish.” (Adams, 2020)

In order to investigate this and other failings further the arts education champion Freelands Foundation has teamed up with race equality think-tank Runnymede Trust to compile a report on inequality in arts education in the UK, the results of which are due to be published in 2023. The project involves a call for students, parents and other arts professionals to provide evidence of their own experiences from within the education system. In their project briefing Freelands Foundation refer to the Department for Education’s findings, that in 2021 “just under 40 per cent of children studying art and design at A-levels in the 2019/20 academic year were from minority ethnic backgrounds”, however by the time they arrive at university age that figure drops by over a half, to around 16 per cent (Visualise: Race and Inclusion in Art Education, no date). I would argue that to some extent the same financial pressures to fulfil a more ‘traditional’ career path still remains but I also suspect (and Freelands Foundation agrees with me) that potential students may be discouraged by the lack of representation in the arts, whether it be lecturers, black artists on the curriculum or their perceived relatability to the course content. In recalling her arts education experience multidisciplinary artist De’Anne Crooks reported;

“I struggle to recall seeing black British artists and black art as a genre in education. GCSE level, A Level, Foundation level, Undergraduate education and Postgraduate education; I have been through these stages of education and studied art (including historic elements of art) at each level and not once was I taught about or saw people of colour in paintings and other forms of visual art.” (Crooks, no date)

In her book ‘Towards an Inclusive Arts Education’ Dr Kate Hatton admits that “Whiteness is little discussed in art education, particularly in relation to institutional structures, staff hierarchies and curriculum emphases” (Hatton, 2015); the resistance to any such inward examination can only stifle any hopes of change within the education system, instead reinforcing and justifying the status quo. An increasing number of scholars in the UK have been turning their attention to Critical Race Theory in order to further explain how an education system dominated by whiteness favours less for children of African and Caribbean descent. The concept (otherwise known as CRT) was developed in the United States by civil-rights scholars in the 1970’s as a means of considering how establishments such as law enforcement, education and the media (to name a few) have designed within them structures and policies driven by racially motivated misconceptions. Within the education system this has manifested itself into an unacceptably low number of black lecturers and students on campus. CRT’s treatment of race as a social construct encourages institutions to address this void through acknowledgment that perspectives have the real power to influence decisions. Thus for any sustainable change to take place art institutions have to examine, understand and challenge their own frame of reference.

With the principles of CRT in mind the charity Advance HE (AHE) was formed in 2003 as a watchdog charged with holding the higher education sector accountable for the wellbeing and advancement of its students and teaching staff (Race Equality Charter, no date). Amongst their achievements was the creation of the Race Equality Charter (REC) touted with the objective of providing “a framework through which institutions work to identify and self-reflect on institutional and cultural barriers standing in the way of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic staff and students.” (Race Equality Charter, no date) Universities who choose to participate in the scheme gain the opportunity to obtain a bronze or silver award depending on their level of advancement towards improved standards and opportunities for its ethnic minority staff and students. In order to qualify for a REC award participating universities are required to satisfy AHE’s ‘five fundamental guiding principles’; these include recognition that “UK higher education cannot reach its full potential unless it can benefit from the talents of the whole population and until individuals from all ethnic backgrounds can benefit equally from the opportunities it affords.” (Race Equality Charter, no date) This is perhaps the most essential of AHE’s philosophies as it takes into account the validity of the black experience and places emphasis on addressing the disparity which exists between socioethnic groups within the UK’s higher education system. The scheme however is voluntary, with only 98 out of the 380+ UCAS registered universities and colleges in the UK participating. A lot can be read into this however without the burden of obligation being enforced we have to accept that some institutions may not view themselves as being in need of such an initiative, or are simply unaware of the project. Maybe more telling is that of the 98 universities that have subscribed to Advance HE’s Race Equality Charter; two-thirds (including, as of 2022, University of the Arts London) have yet to receive either of the attainable accolades (Race Equality Charter, no date). One can surmise from this that there still remains little appetite for change towards a curriculum which engages all students regardless of race and ethnicity.

5 Opportunity Knocking?

Regardless of whether one engages with academia or not emerging and established black artists often find themselves battling against the industry’s attempts to pigeonhole their work into categories that fit the narrative of racial stereotypes. It then comes as no surprise that tangible and sustainable opportunities remain scarce for these minority ethnic artists. For some the prospect a lifetime clambering over hurdles proves too much, in order to increase the chances of advancing their creative careers they sometimes head for pastures new. Frank Bowling, F.N. Souza and Winston Branch made new homes in the United States and found they were more favourably received (Chambers, 2014, p. 80), but it wasn’t just visual artists making this decision, many British musicians felt that the only way to progress their careers was to up-sticks and leave the country that’s offered them very little. Despite suffering its own issues around racial equality attitudes within the US industry were less conservative, and with a larger audience sympathetic to ‘ethnic arts’ the potential for opportunities and for a chance to nurture a career remained (and for some still remain today) enough of an incentive to leave the UK.

In 2021 equalities think-tank Black Lives in Music carried out a survey on 1,718 black musicians and industry professionals, the largest such survey ever conducted in the UK (Black Lives in Music, no date). The survey was triggered by the experience of two African-American music executives who were busy fighting their own campaign for equality in the industry. Brianna Agyemang and Jamila Thomas had joined forces declaring that they could no longer “conduct business as usual without regard for black lives,” making particular reference to “the long-standing racism and inequality that exists from the boardroom to the boulevard” (Black Lives in Music, no date). Their efforts culminated in the creation of the movement TheShowMustBePaused which declared Tuesday, June 2, 2021 a day of action where supporters were encouraged to post nothing on their social media accounts other than a blank black square accompanied with the hashtag #theshowmustbepaused (Mitchell, 2020). The protest was intended to force music industry executives to look inwards and examine the level of systemic racism that exist within their organisations whilst questioning how complicit their actions were.

The BLiM survey confirmed what was already largely felt within the music community, the figures showed that;

86% of all Black music creators agree that there are barriers to progression. This number rises to 89% for Black women and 91% for Black creators who are disabled.

Three in five (63%) Black music creators have experienced direct/indirect racism in the music industry, and more (71%) have experienced racial microaggressions.

35% of all Black music creators have felt the need to change their appearance because of their race/ethnicity, rising to 43% of Black women.

White music creators are 32% more likely to have a music-related qualification than their Black colleagues.

21% of Black music creators earn 100% of their income from music compared to 38% of white music creators.

19% of Black female creators earn 100% of their income from music compared to 40% of female white music creators. This figure drops to 17% if you are a Black and disabled music creator.

(Black Lives in Music, no date)

BLiM’s findings highlighted the extent to which the music industry holds little regards for the contributions of its black musicians and professionals. But even in the absence of such surveys it’s difficult to ignore the fact that racism within the industry exists, inequality continues to plague minority ethnic people and this hinders them from reaching their true potential. Many have cited a lack, or absence of any forms of mentorship or guidance, together with repeated microaggressions as reasons for them feeling undervalued and ignored (Black Lives in Music, no date). Artists such as Nigerian-Welsh R&B singer Kima Otung, who was asked to change her name in order to fit her label’s preferred image, feel that their identity is under attack and they are being coerced into fitting someone else’s blueprint of what black artists are supposed to be (Morgan, 2021).

Such acts of discrimination go beyond how an artist chooses to be addressed, award winning songwriter Carla Marie Williams recalls being told in no certain terms to change her appearance; “I wanted to be a rock soul artist and got my lip pierced very young so then it was like ‘You're not supposed to look like that, you’re supposed to look like this and be like that.’ I was like, what is the stereotypical ideology of what a Black woman should look like?” (Morgan, 2021). Williams overcame pressure from the music executives forging her own identity and pushing her narrative as a ‘rock soul’ star; her determination would lead to collaborations with A-list artists such as Beyonce and Kylie Minogue who she penned songs for (Morgan, 2021). Williams later founded the movement ‘Girls I Rate’ who’s mission was to provide a safe space where female artists could network and nurture their careers without compromise to their chosen identities. In an article which featured in the Guardian newspaper in 2016 Williams concluded;

“By launching Girls I Rate I’m empowering myself and my peers to create change in our corners of the world. The harsh truth is that unless we become one voice and one community working to advance the industry rather than the self without the barriers of gender and race, we’ll be having the same conversations this time next decade.” (Williams, 2016)

Obstacles permeate all sectors of the industry and each level within their respective hierarchy’s. Channel 4 began broadcasting in the UK in 1982, billed as the UK’s fourth terrestrial service with its prime mission to mirror the cultural landscape and makeup of the British Isles through its dynamic and engaging programming aimed at a diverse audience (About Channel 4, no date). The corporation’s mission statement claimed “Our purpose is to create change through entertainment. We do this by representing unheard voices, challenging with purpose and reinventing entertainment” (About Channel 4, no date). Whilst the broadcaster on the whole appeared to succeed in its goals on-air, the makeup of the corporation’s senior management struggled to reflect its ambitions in terms of inclusivity. In 2016 things looked as though they were about to change when it became known that amongst the channel’s five newly appointed non-executive directors was a highly qualified and experienced public sector executive, Althea Efunshile CBE. The TV regulator Ofcom, responsible for recruiting Channel 4’s non-executive directors, was about to appoint who would be the only minority ethnic person on the channel’s board; a decision which seemed to signal a positive step towards addressing the absence of diversity within their senior management team (Sweney, 2017). This decision however, was vetoed by the government’s culture secretary at the time, Karen Bradley. The official explanation stated that Efunshile did not satisfy the criteria set out at the beginning of the selection process, this statement raised eyebrows with many including backbench MP David Lammy who demanded an explanation of the events leading to the minister’s decision to block the proceedings; “how exactly did the four accepted candidates appointed to the board meet the criteria set out by Ofcom, yet Althea failed to meet the same criteria?” asked Lammy, “What vetting did the department carry out in relation to these five candidates to come up with this ridiculous decision?” (Brown, Higgins and Sweney, 2016) Ofcom’s role in appointing Channel 4’s Non-Executive Directors works in tandem with the Department of Culture, Media and Sport who essentially has the last say. The decision to halt Efunshile’s path to the boadroom left many questioning the government’s motive, the decision a year later to appoint Efunshile to that same board was seen as a victorious act by many, and an act of tokenism by others.

6 Brand New Day

The corporate wave of racial awareness and activism that followed in the wake of the public murder of African-American citizen George Floyd carried with it the stench of opportunism; Sainsbury’s Christmas 2020 advertising campaign entitled “Gravy Song” featured a telephone conversation between a father and daughter where they share Christmas memories, what made this advert different (causing complaints from some loyal Sainsbury’s customers) is the fact that the family was black. Yet despite their efforts to appear ‘woke’ in their advertising campaigns Britain’s second biggest grocers admit that “ethnically diverse colleagues make up only 8% of our senior leadership” (Sharing our Ethnicity and Gender Pay Report 2020, 2020). This on-screen exploitation of black faces illustrates the lengths companies are prepared to go to in order to present themselves as morally in-tune and protect their revenue. Sainsbury’s and indeed many other high profile brands continue to cram as many black bodies in front of the camera feigning support for diversity, yet this forced appetite for change hasn’t quite made it to the boardroom.

This exploitation of black bodies for one’s own benefit can play out on a more personal level, as was the case with British contemporary visual artist Marc Quinn and his infamous sculpture ‘A Surge of Power’. The period following George Floyd’s execution saw many protests take place on UK streets; one such gathering saw crowds topple a statue of slave trader Edward Colston which took pride of place in Bristol city centre. One protester placed a knee on the neck of Colston mimicking the actions of the police officer who did the same to Floyd for more than nine minutes, the nine-foot bronze statue was then tossed into Bristol Harbour. The statue’s “drowning” draws parallels to the treatment of slaves crossing the Atlantic, many of whom were discarded overboard after becoming sick or dying, in order for the slave ship owners to be able to claim insurance on their lost ‘cargo’. Colston’s statue was briefly replaced by a sculpture by Quinn entitled “A Surge of Power”. The statue re-enacted the moment that protester Jan Reid mounted the empty plinth in an act of jubilation raising her clenched fist in the air. Reid’s image later went viral flaunting the attention of the accomplished British visual artist who felt inspired to cast the statue. Quinn, a white man, had previously shown little interest in supporting the Black Lives Matter movement, or any other protest or organisation prior to the events that took place in Bristol on June 7 2020, his work typically does not incorporate elements of protest, more observation (Morris, 2020). The mayor of Bristol, Marvin Rees, pleaded with Quinn to reconsider mounting his 7.5-foot black resin statue citing the potential for racial tension, and British Sculptor Hew Locke took to Twitter to vent his frustrations as follows “The people of Bristol were not consulted, it feels arrogant… It is as much to do with the sculptor’s ego than it is about BLM” (Morris, 2020) Further accusations of cultural appropriation for personal reward followed.

On the other side of the coin some positive moves have been made by galleries and museums across Europe to bring to the forefront the role of blackness within art history; addressing the absence of recognition afforded to people of colour and their contributions. Recent exhibitions like In the Black Fantastic (Hayward Gallery, 2022) and Life Between Islands (Tate Britain, 2021/2) have put black art centre stage and many new artists are enjoying a renewed appetite for their work to be seen by an arguably more enlightened audience. Further afield, in March 2019 the Musée d'Orsay in Paris staged an exhibition billed as ground breaking in its attempt to award the black model some dignity and rightful recognition. The curators of Black models: from Géricault to Matisse carried out extensive research in order to identify the models featured in their collection followed by renaming the paintings (Black models: from Géricault to Matisse, no date), albeit temporarily. Manet’s ‘Olympia’ became ‘Laure’ in recognition of the black maid that appears in his 1863 masterpiece (Black models: from Géricault to Matisse, no date). As discussed earlier Laurie, like many others would have been seen as objects within a scene, unimportant, and this would have been reflected in the titles to works such as ‘Portrait of a Negress’ (Marie-Guillemine Benoist, 1800). The exhibition offers the visiting public an insight into the extent at which these identities were written out of the art-history books.

But despite all of this my fear is that these exhibitions, artists and subjects may too fall into obscurity; history has a habit of repeating itself and with the onset of Brexit and the detrimental effects of a growing nationalistic pride it’s not too difficult to imagine how racial tensions may undermine any efforts to eradicate marginalisation. Whilst it’s true that art bears the potential to unite people and offer insight into the lives of others it still appears to be one of the most likely targets for racism.

Conclusions:

The arts have long been associated with wealth, memorials pay homage to this notion where only the great (usually wealthy, male and white) are honoured in marble or bronze. Any detailed studies of the historic involvement or achievements by black artists have been largely omitted, restricted to those documented by special archives and not easily obtainable. This inevitably plays heavily on the psyche of people of colour in the industry who have access to few points of reference, leading to questions regarding where they fit in.

One of the difficulties I faced whilst writing this paper was the lack of available materials at my disposal, in some instances a pitiful amount of data exists. My research into the Trinidadian painter Roy Caboo one such instance where I found only two Google Scholar articles and a handful via Google’s main search engine. This reaffirming my position regarding the curse of obscurity that faced the pioneers of minority ethnic arts. Today the nature of the internet gives hope that the likes of Chris Ofili and Heather Agyepong need not suffer the same fate. But even with that glimmer of positivity we have to consider the possibility that the industry may fall back on old habits casting lesser-known manes into invisibility, or bestowing recognition after death.

Education has a chasm to plug in terms of the curriculum and the recruitment of an inclusive workforce; the education system is broken, it holds as its core the ability and willingness for the student to comply with the status quo. Those who feel alienated from the curriculum will be amongst those most likely to fall out of reach of the expected standards. A curriculum which on the whole fails to acknowledge their histories and experiences as well as ignoring the wealth of contributions made to the British arts movement. In an education system with little representation to grasp it remains no wonder that so few students of minority ethnic backgrounds aspire to engage in arts education beyond secondary school, and fewer see teaching art as an attractive career path. And lest not forget that education is in many respects operates as a closed shop, with the rights to knowledge being closely guarded; those with enough capital (whether earnt, saved or borrowed) stand more chance gaining access to its fruits. In conducting research for this document I found that many of my sources were only available through the use of my university login; anyone attempting to broaden their own education outside of a recognised establishment would find this a challenging activity.

But what to replace it with? Whilst I do not claim to have a magic solution to the shortcomings of the arts education machine I do believe that we should be striving towards one that recognises creative ability over conformity, one that is truly inclusive and respectful of students ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds. Such a revival would require a complete overhaul of the curriculum, possibly scripted by student bodies, a dynamic curriculum that updates itself and remains relevant and reflective of the current landscape. Maybe the offer of a modular system, where students are able to select the areas of study with a more focussed selection available which addresses culturally influenced topics. Initiative such as Advance HE’s Race Equality Charter play a vital role in the fight to level up the playing field, no dean wants to see their institution ranking low in any category by which enrolment rates might be affected, but one can argue that it’s easy for any establishment to employ more black lecturers in order to qualify for an award than it is to make real and sustainable changes to its own historic sets of ethics and institutional culture.

It's clear that for real change to take place in the arts industry there has to be instilled a new culture of inclusivity, this has to happen from the top down to be effective. It beggars belief that an organisation like Channel 4 could operate prior to 2016 with no black leadership given their mission to “mirror the cultural landscape and makeup of the British Isles”. It can be argued that the landscape has improved for black artists in the UK, there have been some improvements in regards to exposure and inclusivity, however I remain convinced that there lies plenty of scope for more growth. Whilst the events of 2020 saw many galleries and media outlets featuring the work of the new breed, the expectation still remains for black artists to produce identity driven work, or band together as a collective, in order to be taken seriously and gain gallery space. The UK art scene is yet to accept the presence of blackness as a part of its history, and to that we still remain marginalised. Considerations such as these are not generally imposed upon white British artists and therefore there remains some misalignment between their work and that of the minority ethnic artist.

In some respects, I can see some benefits of a self-imposed marginalisation; black artists should maybe consider joining forces once again and championing the rights to their place on the agenda, like the pioneers of the BLK Art Group did in the 70’s/80’s. However, I fear that we may have become possibly too concerned with our individual pursuits, gone are the days when we felt a commonality with each other. Even within the UK’s black community ethnic division is clear, skin colour not being the common unifier it used to be. Five decades and four generations later, we may seem more woven into the fabric of society but at what expense?

Bibliography:

About Channel 4. (no date) Available at: https://www.channel4.com/corporate/about-4/who-we-are/about-channel-4 (Accessed: 3 January 2023).

Adams, R. (2020) Fewer than 1% of UK university professors are black, figures show. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/feb/27/fewer-than-1-of-uk-university-professors-are-black-figures-show (Accessed: 25 October 2022).

Baksi, C. (2021) The story of the Zong slave ship: a mass murder masquerading as an insurance claim. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/law/2021/jan/19/the-story-of-the-zong-slave-ship-a-mass-masquerading-as-an-insurance-claim (Accessed: 21 December 2022).

Bhopal, K. (2022) We can talk the talk, but we’re not allowed to walk the walk’: the role of equality and diversity staff in higher education institutions in England. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00835-7 (Accessed: 5 January 2023).

Black Lives in Music. (no date) Available at: https://blim.org.uk/about-us/ (Accessed: 9 January 2023).

Black models: from Géricault to Matisse. (no date) Available at: https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/exhibitions/black-models-gericault-matisse-196083 (Accessed: 22 January 2022).

Boyall, J. (2020) Crossing boundaries: the life and works of Aubrey Williams. Available at: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/crossing-boundaries-the-life-and-works-of-aubrey-williams (Accessed 2 December 2022).

Brett, G. (2003) A reputation restored: The rediscovery of sculptor Ronald Moody. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/ronald-moody-2298/reputation-restored (Accessed: 22 October 2022).

Brown, M., Higgins, C and Sweney, M. (2016) Blocking of Althea Efunshile from C4 board 'beggars belief', says MP. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2016/dec/07/blocking-of-althea-efunshile-from-c4-board-beggars-belief (Accessed: 3 January 2023).

Chambers, E. (2014) Black Artists in British Art: A History from 1950 to the Present. London: I.B.Tauris.

Clay, S. (2018), ‘”So, You Want to be an Academic?” The Experiences of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Undergraduates in a UK Creative Arts University’, in S. Billingham (ed), Access to Success and Social Mobility through Higher Education: A Curate's Egg? [PDF version]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-78743-836-120181009 (Accessed: 15 January 2023).

Crooks, D. (no date) Representation in art education: The absence of black art. Available at: https://www.yellowzine.com/post/representation-in-art-education-the-absence-of-black-art (Accessed: 20 December 2022).

Equiano, O. (2015) The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano: or, Gustavus Vassa, the African. London: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform

France-Presse, A. (2019) French masterpieces renamed after black subjects in new exhibition. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/mar/26/french-masterpieces-renamed-after-black-subjects-in-new-exhibition (Accessed: 22 December 2022).

Fullerton, E. (2019) ‘I'm almost enjoying myself!' – Frank Bowling's six-decade journey to success. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/may/29/frank-bowling-painter-six-decade-journey-to-success-tate (Accessed 11 October 2022).

Hatton, K. (ed) (2015) Towards an Inclusive Arts Education. London: Trentham Books.

Hissong, S. (2020) Blackout Tuesday’s Founders Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang — Future 25. Available at: https://www.rollingstone.com/pro/features/blackout-tuesday-jamila-thomas-and-platoon-brianna-agyemang-future-25-1079717/ (Accessed: 4 January 2023).

Household income. (2022) Available at: https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/work-pay-and-benefits/pay-and-income/household-income/latest (Accessed: 20 September 2022).

Hylton, R. (2019) Decolonising the Curriculum. Available at: https://www.artmonthly.co.uk/magazine/site/article/decolonising-the-curriculum-by-richard-hylton-may-2019 (Accessed: 12 November 2022).

Joseph, P. (2019) The outrageous neglect of African figures in art history. Available at: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/the-outrageous-neglect-of-african-figures-in-art-history (Accessed: 10 November 2022).

Keaney, E. (2008) ‘Understanding arts audiences: existing data and what it tells us’, Cultural Trends, 17, pp. 97-113. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09548960802090642 (Accessed: 15 January 2023) .

The Keskidee Centre. (2020) Available at: https://friendsofim.com/2020/06/12/refugee-week-2020-2/ (Accessed: 27 October 2022)

Khan, N. (1976) The Arts Britain ignores: the arts of ethnic minorities in Britain. London: Commission for Racial Equality.

Lloyd, E. (2018) Caribbean Artists Movement (1966–1972) Available at: https://www.bl.uk/windrush/articles/caribbean-artists-movement-1966-1972 (Accessed: 15 December 2022).

Madin, J. (2006) The lost African, slavery and portraiture in the age of the enlightenment. Available at: https://d3d00swyhr67nd.cloudfront.net/_file/The-Lost-African-Apollo-article.pdf (Accessed: 10 November 2022).

Madin, J. (2019) John Madin responds to our article about 'Portrait of an African'. Available at: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/john-madin-responds-to-our-article-about-portrait-of-an-african (Accessed: 10 November 2022).

Manet’s Olympia Laure and Victorine. (2020) Available at: https://pallant.org.uk/manets-olympia-laure-and-victorine/ (Accessed: 22 December 2022).

Mitchell, G. (2020) The Women Behind #TheShowMustBePaused - And What They’re Planning Next. Available at: https://www.billboard.com/music/music-news/the-show-must-be-paused-founders-billboard-cover-story-interview-2020-9399509/ (Accessed: 10 January 2023).

Moody, C. (1998) ‘Midonz’, Transition, 77, pp. 10-18. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/2903197 (Accessed: 15 January 2023).

Morgan, M. (2021) I was told to shut up & write songs: Black artists on racism in the UK music industry. Available at: https://www.refinery29.com/en-gb/black-musicians-racism-uk-industry (Accessed: 10 January 2023).

Morris, K. (2020) Marc Quinn’s Black Lives Matter Statue Is Not Solidarity. Available at: https://artreview.com/marc-quinn-black-lives-matter-statue-is-not-solidarity/ (Accessed: 22 December 2022).

Race Equality Charter. (no date) Available at: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/equality-charters/race-equality-charter (Accessed: 22 December 2022).

Sharing our Ethnicity and Gender Pay Report 2020. (2020) Available at: https://www.about.sainsburys.co.uk/~/media/Files/S/Sainsburys/Gender%20Ethnicity%20Pay%20Gap%20Report%202020.pdf (Accessed: 20 November 2022).

Sinclair, L. (2020) The BLK Art Group: how the West Midlands collective inspired the art world. Available at: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/the-blk-art-group-how-the-west-midlands-collective-inspired-the-art-world (Accessed: 3 January 2023).

The Slave Trade and Abolition. (no date) Available at: https://historicengland.org.uk/research/inclusive-heritage/the-slave-trade-and-abolition/ (Accessed: 4 January 2023).

Sweney, M. (2017) Althea Efunshile joins Channel 4 board after government U-turn. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2017/dec/12/althea-efunshile-channel-4-board-culture-secretary (Accessed: 3 January 2023).

Visualise: Race and Inclusion in Art Education. (no date) Available at: https://www.runnymedetrust.org/partnership-projects/visualise-race-and-inclusion-in-art-education (Accessed: 8 December 2022).

What Is UCAS? (no date) Available at: https://www.ucas.com/about-us/who-we-are (Accessed: 12 December 2022).

Williams, C.M. (2016) For black women in music it's hard to defy the stereotype. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/women-in-leadership/2016/feb/29/carla-marie-williams-for-black-women-in-music-its-hard-to-defy-the-stereotype (Accessed: 2 January 2023).

Comments